Posted January 22, 2025

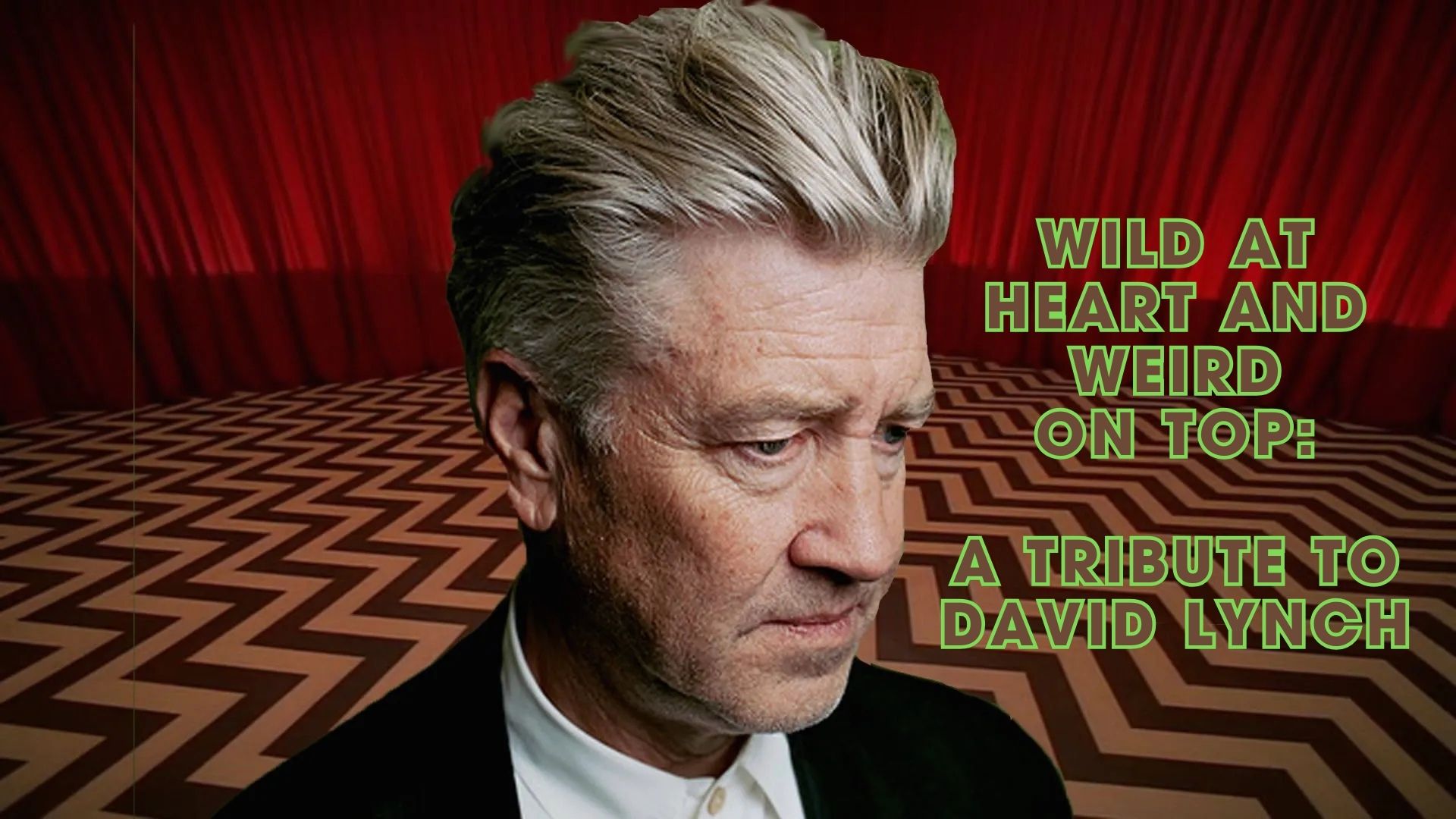

Wild at Heart and Weird on Top: A Tribute to David Lynch

by JBFC Marketing Manager Paige Grand Pré

When I heard the news that David Lynch had passed, it took everything in me not to weep at my desk. As with David Bowie’s death, it was shocking simply because it was hard to even think of David Lynch as mortal; he seemed to exist on another plane of existence entirely, one far removed from the trifling, quotidian troubles of us mere humans. The fact that I have a “Welcome to Twin Peaks” sign bobblehead mounted atop my desktop computer only made reading tributes to him throughout the day harder. Yet I couldn’t help thinking that Lynch would’ve loved the cruelly ironic juxtaposition of my goofy bobblehead against the brutal finality of his obituary. I realized Lynch’s death was hard to process not only because his works have meant so much to me over the years, but also because he had literally recalibrated the way I think about film, art, and life—even now, after his passing, I was comforting myself with the thought that he’d like the dark humor of my desktop tableau, as though he was an old friend I knew intimately and not a celebrity with whom I’d never spoken.

So much has already been said about David Lynch as a visionary: how he seamlessly blended the morbid with the mundane to dazzling yet discomforting effect, how his vision was so singular, so unique, that “Lynchian” quickly became an adjective to describe the dark undercurrents that lurk beneath our placid, petty existence. After all, how many other artists have created their own genre?

He was a visionary in the purest sense of the word, but he was also so much more. He was a gateway drug for movie lovers dipping a toe into the world of art films, a conduit that brought magical realism to the masses, an enigmatic idol around whom oddballs convalesced and over whom they bonded, and a true lover of life. He was occasionally criticized for being too opaque, too abstract, too avant-garde. But these critiques conflate surrealism with inaccessibility, which couldn’t be further from the truth. To Lynch, the more abstract an idea, the more people could engage with it—precisely because it defied straightforward interpretation. For someone who is arguably the most famous and impactful art film director of all time, he was violently allergic to pretentiousness.

For Lynch, a nonconformist whose eccentricities made other misfits feel less alone, there is no distinction between high and low art. How else could he have created heavy-hitting cinematic masterpieces like Mulholland Drive (2001) or Blue Velvet (1986) while also elevating the melodrama of soap operas to the status of art films with Twin Peaks (1990-1991) and Twin Peaks: The Return (2017)? Many posthumous tributes have noted how, despite Lynch’s demonstrated eloquence, he rarely commented on or analyzed his own work. As Kyle MacLachlan noted, “words were insufficient;” he’d released it in the language of cinema, after all, and believed that the work spoke for itself. The work wasn’t even necessarily meant to be understood or analyzed—it was to be felt, experienced, absorbed, pondered, replayed over and over as you tried (surely, in vain) to answer all the questions it raised. Don’t understand a Lynch film? Good. That’s the point.

That’s the beauty of David Lynch—never wanting to “put his thumb on the scale,” he vehemently resisted explicit explanations of his work, and rejected suggestions that there was any one single interpretation of his narratives. He wanted us to project our own meaning onto his art, hoped that we would parse out themes and ideas that even he hadn’t considered, and loved the idea that a single work could produce such a multitude of interpretations. That way, his work could mean something to everyone—which is, I think, why Lynch’s death has produced such profound and widespread mourning among art and film fans of all ages, and why his works will continue to resonate for generations to come. No one individual holds a monopoly on understanding Lynch’s work—David Lynch is for everyone.

But even more than that, I think what makes David Lynch—as an artist and an individual—such an enduring figure is the fact that at the core of all these dark, twisted works that probed the depths of our souls was a loving individual whose joie de vivre was so saccharine it almost seemed insincere. He took pleasure in the little things—coffee, cigarettes, local radio stations, pieces of pie, sunshine—and encouraged others to do so, too. He approached every aspect of his art, relationships with others, and life with a level of endearing enthusiasm that feels almost ironic for a “serious” artist of his stature. But he was as genuine as they come. He navigated the world with a sense of childlike wonder and uninhibited joy, but the darkness of his works makes clear that this eagerness and sincerity was not the product of naïveté. To be sure, he understood the depths of despair all too well; rather, his optimism was the result of staring into the void and hoping—nay, believing—that we could be better. That even in darkness, there is light. That pain, trauma, horror, and agony coexist with joy, triumph, laughter, and love. And in the space in between? That’s where art lives. Lynch was not afraid to feel things—he just wanted us all to feel them, too.

By all accounts, he was a pleasure to work and spend time with. He had his crews on set applaud every performance after a scene had wrapped, and he told people—from muses and frequent collaborators to mere extras just passing through—that he loved them, early and often. He argued that no one should suffer for their art: that there is enough suffering in the world already, an artist needn’t be tortured to create something of value, and that suffering may even inhibit the creative process to the point where pain is unproductive. He reminded artists to practice self-care before the concept had even really entered the zeitgeist. He encouraged others to meditate in hopes of finding inner peace or healing, to know thy selves, to dive deep in search of inspiration, to make art—however bad—in an attempt to express yourself, to “fix your hearts or die.”

It is Lynch’s unshakeable belief in the cathartic power of art, and the importance of creating art for art’s sake, that makes him such an anomaly in an increasingly commercialized artistic landscape—and exactly what makes him so worthy of hero worship. David Lynch is an artist’s artist and a filmmaker’s filmmaker, but above all else he saw, believed in, and encouraged the artist in all of us. How lucky we are to have shared the sky with a star that burned so bright.

Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole.

DAVID LYNCH FOREVER.

Celebrate David Lynch’s life and legacy with an in memoriam double feature at the Jacob Burns Film Center on Sunday, March 16: A 3:00 screening of Blue Velvet will be followed by a Q&A with Director of Photography and Cinematographer Frederick Elmes; afterwards, at 6:30, Elmes will introduce Wild at Heart, which will screen on Elmes’ personal 35mm print.