Posted December 9, 2025

The Secret Agent: Exorcising the Boogeymen of Pernambuco

JBFC Programming Administrative Assistant Filipe Galhardo shares context on the Golden Globe nominated & Cannes winning film The Secret Agent, opening at the JBFC on Dec. 12.

I could not have been more excited to see The Secret Agent. Not only am I a tremendous fan of director Kleber Mendonça Filho’s previous feature, the wickedly sharp genre-bending social satire Bacurau (2019), but the success surrounding The Secret Agent at Cannes only added to my excitement – as both a cinephile and native Brazilian. It was very surreal for many Brazilians to see Wagner Moura, Kleber Mendonça Filho, and the rest of the film’s cast dancing the Frevo, an iconic carnival dance that is a staple of Pernambuco culture, down the streets of Cannes on their way to the film’s premiere.

The state of Pernambuco, and its capital city of Recife in particular, is the setting of The Secret Agent and many other of Mendonça Filho’s films. It’s also the homeland of my mother’s side of the family and the city in which my parents met. I’ve never lived there, but since moving to the US at the age of five it’s a city I’ve visited almost every summer of my adolescent life.

I grew up hearing stories from my mother about growing up in Recife, including “the time of great mischief” depicted on screen in The Secret Agent. I heard second-hand stories about all of the good, as much of the bad as you can comfortably tell a child, and plenty of the in-between. I absorbed enough cultural context that I was able to share some additional information about the weight of some of the imagery and themes explored in the film to my colleagues. Now, I’d like to share that additional context to you all.

Spoilers ahead. I encourage anyone interested to watch this truly spectacular film first if they’d like to avoid spoilers, then come back. Major Spoilers concerning the film’s resolution are marked.

Recife is somewhat famous for things that go bump in the night. The fifth largest city in Brazil with a nearly five hundred year old colonial history; Recife has a rich tapestry of folkloric figures, hauntings, and urban legends. At the same time it’s also a city whose people have struggled with the constant fear of real tangible dangers almost too numerous to name: poverty, street violence, political corruption; even acts of God.

The interplay between the fears of imagined or exaggerated threats and the dangers of real life violence are a main focus of The Secret Agent. Mendonça Filho explores this through two iconic symbols of fear intrinsically tied with the history and culture of Recife: sharks and the Hairy Leg—elements of the film that international audiences may not fully understand on a first watch.

Like many cities in Brazil, Recife is home to some truly beautiful beachfront locales. Unfortunately, what lingers in the popular Brazilian consciousness are not the beautiful locales of Boa Viagem beach but the real danger of shark attacks that have plagued the city since the 90s. Once a swimmer’s and surfer’s paradise, the construction of a port in the late 1970s (around the time of the events depicted in The Secret Agent) led to environmental changes that caused the beaches of Recife to become one of the deadliest shark attack hotspots in the world.

Surfing has been altogether banned in most of the city’s beaches out of an abundance of caution and signs advising against swimming in the water can be seen all over the city’s major beaches. I remember going in the water but never far enough to submerge. I thought if I only went as far as my waist I would be safe. Even then, stories of sharks dragging their bodies across the sand to attack children in the shallow waters of the beach were shared like ghost stories. As a child I knew that the warnings were there for a reason, but the constant anxiety stemming from the threat of danger was a greater weight on my mind than the possibility of actually being attacked.

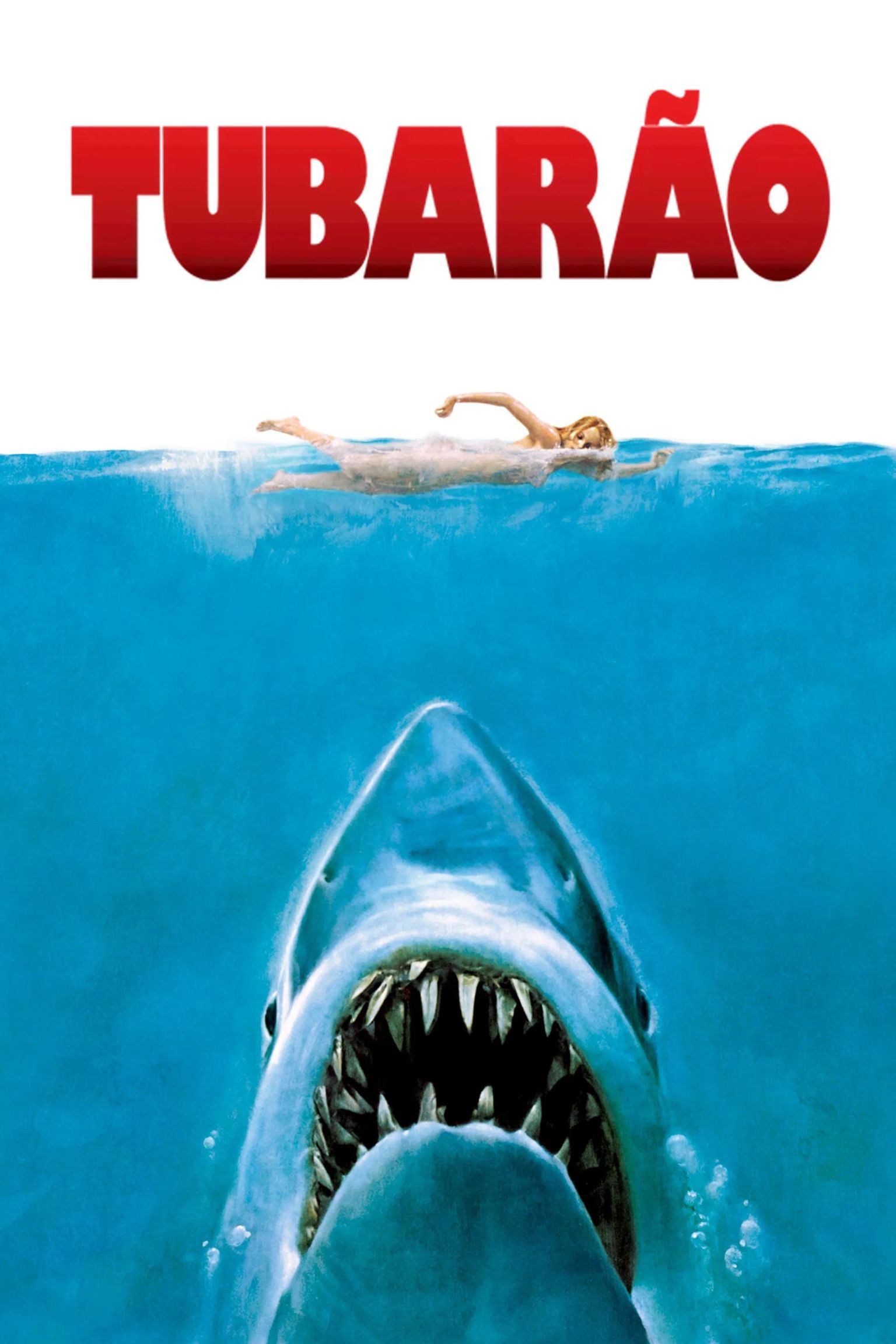

Sharks are an interestingly anachronistic motif in The Secret Agent. The deadly shark attacks that would make Recife’s beaches infamous would not yet begin for decades, but there is a good reason for their inclusion in the film. Before they were ever a real danger, the fear of sharks stalked their way into the imagination of audiences world-wide through the success of Spielberg’s Jaws (Tubarão in Portuguese), which was released during the era The Secret Agent is set. Wagner Moura’s Marcelo has a young son named Fernando who is both fascinated by and terrified by imagery from Jaws. He draws the film’s poster over and over while constantly seeing sharks in his dreams. Mendonça Filho draws attention to this: act one of the film is titled “The Boy’s Nightmare”.

The shark in the film introduces the audience to a major plot point and another icon of Recife that necessitates further explaining. For those wondering what the hell the Hairy Leg (Perna Cabeluda) is about, I’m sure you’re not the only one. I found myself surprised and delighted at how little explanation the Hairy Leg was given in the film before its horrible and glorious silver screen debut.

The Hairy Leg is a modern folk legend native to Recife, obscure even to the rest of Brazil. It is exactly what it sounds like: a big Hairy Leg that goes around violently kicking and tripping people. In the years since its first “reported sightings” around 1976, this obscure cryptid/apparition has become a point of local pride for those from the city: an aspect captured in the film. When the film’s enclave of political refugees read about the Hairy Leg in the news, they are delighted and fascinated by such a bizarre and quirky example of local folklore. And yet, in the same scene, the woman from Angola Thereza Vitória remarks that something about Recife makes her uncomfortable in a way she can’t quite place.

The truth behind the Hairy Leg likely comes from a much more sinister place. In a conversation with Deadline, Mendonça Filho explains the origin of the beast and its significance in the film: “For most of my life, for all my life, the hairy leg was a local urban legend… Recife had a number of urban legends. The hairy leg was actually created by a local journalist who was so fed up with not being able to write about what happened last night in terms of violence—because, of course, the police or the military inflicted… terror on the gay population, people having sex in parks, smoking pot. And so he developed a ‘hairy leg’ as a code. So, [he would write], ‘The hairy leg struck again last night,’ and everybody knew that something bad related to the police force was involved.”

In the film, the ridiculous yet equally horrific sequence in which the leg doles out violence to the marginalized people of Recife is shot like a slasher movie. All the while the political refugees, themselves vulnerable to state violence, read the story, laugh, and enjoy themselves. Mendonça Filho expertly captures the way in which something birthed from truly horrible acts of violence was transformed into a harmless fairy tale. He is able to have his cake and eat it too: proudly sharing a truly bizarre and unique cultural figure of Pernambuco without sanitizing the real climate of political violence it was birthed from.Mendonça Filho even walked the red carpet with the Hairy Leg itself in tow.

Kleber Mendonça Filho with the Hairy Leg in tow for the Brazilian premiere of The Secret Agent at the São Paulo International Film Festival. (Photo Credit: Daniel Teixeira/Estadão)

The shark and the Hairy Leg are introduced to the audience together as a package. Representing tangible representations of the fear of political repression made manifest. The Hairy Leg’s real life origin as a coded signifier for police violence is tied to its thematic inclusion in the film, but its diegetic origin in the film as the severed and bloated leg of a young man murdered by the police makes the significance even clearer. As depicted in the film, the corpses of many of those murdered by the military regime and their cronies in Brazil were disposed of in bodies of water: a strategy also practiced by the military dictatorship of Argentina in their infamous “Dirty War”.The state sponsored murders in Brazil were significantly fewer in number than those in Argentina, but often employed similar methods. By bringing the severed leg of the murdered man back out of the murky waters and into the daylight, the shark, itself a symbol of fear, shines a light on the many more victims that were disappeared by the Brazilian government, the police, and their supporters.

MAJOR SPOILERS

In the film’s third act, “Blood Transfusion”, we are introduced to Fernando as an adult, also played by Wagner Moura, now a doctor working in Recife. The building his clinic operates out of was formerly the street cinema featured in the film, the same cinema where he finally saw Jaws after the tragic and mysterious death of his father. After closing and sitting abandoned for years, it became a clinic: an acknowledgement of the gradually fading landscape of many of Recife’s historical and cultural landmarks, a topic of great interest to Mendonça Filho and the subject of his 2023 documentary Pictures of Ghosts. Fernando tells Flavia, the young archivist documenting the clandestine history of his father’s case, that his childhood nightmares stopped as soon as he saw the film for the first time.

All nations are haunted by the ghosts of the past, but Brazil has suffered uniquely due to never properly exhuming its buried history. The military regime ended not with a glamorous and cathartic revolution, but with a gradual whimper: the government gradually moved towards democracy in great part because many members of the military regime themselves were dissatisfied with the way things were. They ended the dictatorship on their own terms.

During the tail end of the dictatorship in 1979, the military regime passed an amnesty law to help facilitate the change to democracy. Political exiles were invited back to the country and left wing groups – nonviolent activists and radical revolutionaries alike – were legally pardoned for any crimes against the state. At the same time, the amnesty law shielded all members of the military regime and their collaborators from retribution for any action committed during the regime’s reign of terror. High ranking military officials either retired in peace and wealth or seamlessly transitioned into positions of power in the private sector or the new government.

In recent years, Brazil has faced a resurgence of authoritarianism and a call for a return to the politics of the 1970s. Jair Bolsonaro, a former captain in the Brazilian Army during the dictatorship, was elected president of Brazil in 2019. An extreme far-right populist and Brazilian nationalist, Bolsonaro spoke about the regime as good old days he longed to bring back to Brazil. Amongst many other choice sound bites, Bolsonaro famously said the regime was too soft: it should have killed more and tortured less. For those interested in learning more about the rise of the contemporary Brazilian far-right, Petra Costa’s documentary The Edge of Democracy and its follow up Apocalypse in the Tropics serve as wonderfully gripping portraits of a turbulent era.

Less than a decade later in November 2025, only weeks after The Secret Agent was released in Brazil, Jair Boloanaro is now in prison. He began serving his 27 year prison sentence for planning a political coup that involved the assassination of his political rival (and Brazil’s current president) Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, or “Lula” as he is popularly known.

The dramatic rise and fall of Bolsonaro’s political ambitions have caused a ripple effect in popular Brazilian culture and the way the legacy of the dictatorship is discussed. The Secret Agent is in many ways a companion piece to last year’s extremely successful Oscar winning historical biopic I’m Still Here, starring Fernanda Torres as Eunice Paiva, the wife of disappeared political victim Rubens Paiva. Instead of glancing over uncomfortable legacies of the past, Brazilian filmmakers are actively telling stories about the military regime and audiences are showing up to listen.

William Faulkner once wrote that “The past is never dead. It’s not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.” The adult Fernando knows nothing about what happened to his father or the tragic circumstances of his death. In the same vein, Marcelo (whose real name is revealed to be Armando) knew nothing about his mother and spent his final days searching for evidence of her existence. Armando’s mother is just one of many indigenous women exploited and forgotten by Brazilian society, and Armando himself is a victim of a petty vendetta whose violent murder was lost to time.

The “Blood Transfusion” that frames act 3 is a metaphor about the importance of keeping political history alive. It’s something that the archivist Flavia does within the narrative, and also something that Kleber Mendonça Filho does with the entirety of The Secret Agent. While the story is fictional, the characters in it represent the social realities of the average people of Pernambuco. The film’s periodicity isn’t mere set dressing – it captures the reality of a time and place long overdue for representation. There’s something potentially cathartic about the film for those who lived through those years, while those who didn’t can learn about the repressed history of their country. Ignorance of history is not a moral failing, especially in an impoverished nation, but it is a weakness that can be exploited by powerful people with bad intentions. The Secret Agent is a film of imaginative rediscovery that strives to exorcise the boogeymen that haunted the past so that we may better recognize them in the present.

Filipe Galhardo joined the JBFC as a member of the House Staff in 2022 and later the Programming Department as an Administrative Assistant in 2024. Originally born in São Paulo Brazil, Filipe grew up in a small town in Illinois and then southern Westchester. He graduated from NYU Tisch’s Martin Scorsese Department of Cinema Studies in 2020. Filipe has varied tastes and is too indecisive to declare a filmmaker as a definitive “favorite”, but he is a big fan of Federico Fellini. If it were up to him, more people would talk about Ginger and Fred.